Some months ago I wrote about our miserable experience with Netflix. Constant freaking buffering through our admittedly old Roku box.

We tried a number of things to improve performance, including a new N-type router, but the same behavior persisted until we learned to go with the flow, sort of.

Instead of reloading the network, or reloading the stream, the best thing to do was wait: We would start a stream, it would play for a few minutes, grind to a halt, then reload and eventually drop from 4 dots of throughtput to 2 stars. It would then buffer some more and after a couple of minutes, it would work. Usually.

Sylvester Stallone would be grainier. So would Denise Richards. But the show would go on.

This all started happening late last year. At first I thought it was perhaps interference from all the routers in our building and the ones surrounding it. Or a microwave or cordless phone on the other side of the wall.

But the more I diagnosed the cause, it seemed to all come back to the fact that Netflix used to seamlessly adjust the screen resolution based on the amount of available bandwidth, but it was now insisting on running in HD. Despite the fact that Verizon cannot deliver more than 3Mb per second to our house over DSL.

Which is fine. I get HD when I stream on my computer. Barely. But the Roku fails and that seems to be a failure of either Netflix to properly adjust the resolution or Roku to transmit the information.

In any case, as much as I loathe Verizon, they didn’t seem to be particularly to blame here. My bandwidth tests show occasionally erratic bandwidth, but more often not delivery of what I was paying for. And my mlb.tv stream, while far from faultless, wasn’t constantly buffering. It was, in fact, constantly adjusting stream rates so I had a picture. Sometimes really sharp, sometimes pixilated. Usually with inane local banter.

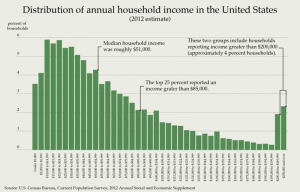

I wrote about this here some months ago (February), mainly my attempt to work out what was going on. And it seemed to make the most sense that Netflix was trying to force the ISPs to provide more bandwidth (Netflix consumers 70 percent of the streaming video volume, and insane amount of total internet use every day) at lower cost. Those that did, had reasonable throughput. Those that wanted to charge Netflix for that throughput, namely Comcast and Verizon, saw throughput drop.

In recent weeks, Netflix started to send an error message to customers saying that the buffering was Verizon’s fault. This caused Verizon to go to court, and before it showed any evidence Netflix withdrew the error message.

Which makes this rather long and somewhat technical story of interest, since it seems to muster numbers that show that the Comcast and Verizon problems for Netflix were actually caused by Netflix. Sort of like I said in February.

As the story concludes, it is based on the available numbers, and those may not be all the numbers. Netflix may actually have good reasons to be negotiating with Comcast and Verizon this way. And it seems likely that there will eventually be a better way to handle the sharing of routes of pipes, called “peerage,” in the future.

For now, we’re stuck with this mess. And I don’t think it unreasonable for Netflix to try to push Comcast and Verizon into better service. These monopolistic giants are a burden to us all, and we would be better off with a different system.

Verizon signed a franchise agreement with the city of New York in 2007 that said it would provide universal fiber optic (FIOS) service throughout New York City by the end of June 2014. Uh oh.

It turns out that FIOS installation is really expensive. Verizon got slammed by our two big storms, Irene and Sandy, but the fact is they’re giving up on FIOS. Having no competition, they can sit on their decaying DSL system, invest less and milk their exclusive franchise until someone sues them for failure to deliver. Which will mean a fine, a cost of doing business, in the future, and leave large parts of New York City a tech black hole, and yet a cash cow, for the phone company.

I want my video now. And if Netflix is messing up my stream, they’re playing with fire. The problem is they have the extinguisher: No video.