I wrote this in January, but didn’t post it then because I was too angry and wanted to let it sit. Then I got distracted by other things, and it sat waiting for attention. Reading it today reminds just how screwy our world can be. So, I hope this provides a laugh. Plus, I got a bill from Verizon the other day. It said I owed .75 cents plus 8 cents tax for a Three Way Call between 1/13 and 2/12, though our service was disconnected on December 20th. I struggled to find a phone number and I struggled to get through the voice-activated phone tree, but eventually spoke with a charming woman in Finance (I had been misdirected). She said (before transferring me to customer service), “Don’t tell anyone I said this, but just tell them that this is too small an amount to write and mail a check, and they’ll take it off. Just don’t tell them I said so, she laughed wonderfully. And I did, and so did they.”

I’m on hold right now, having finally found a way to contact a person at Verizon. The issue today? I cancelled my Verizon phone service on December 20th, but today they pulled money from my bank account automatically for December 13 to January 12. I want a refund for the days after I cancelled service.

I’m on hold right now, having finally found a way to contact a person at Verizon. The issue today? I cancelled my Verizon phone service on December 20th, but today they pulled money from my bank account automatically for December 13 to January 12. I want a refund for the days after I cancelled service.

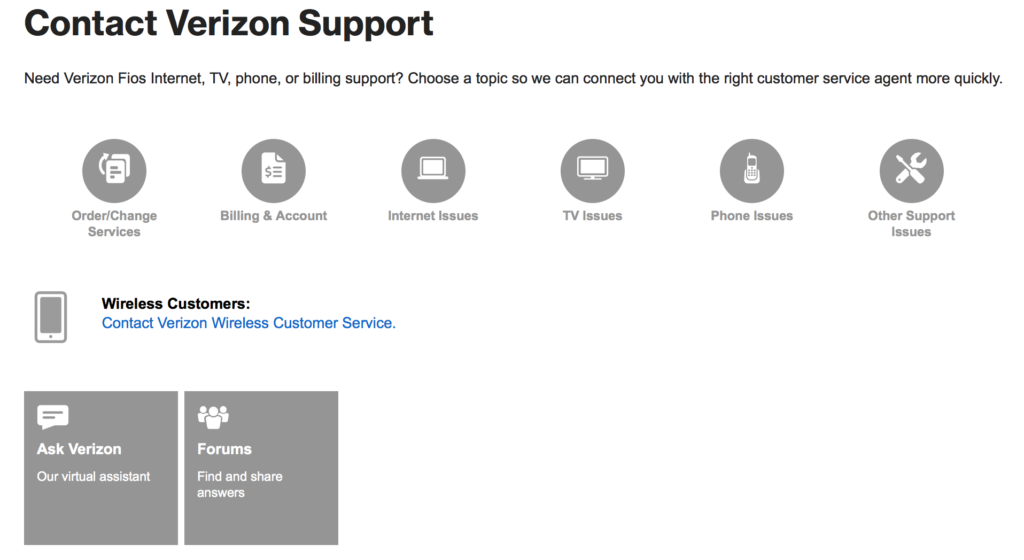

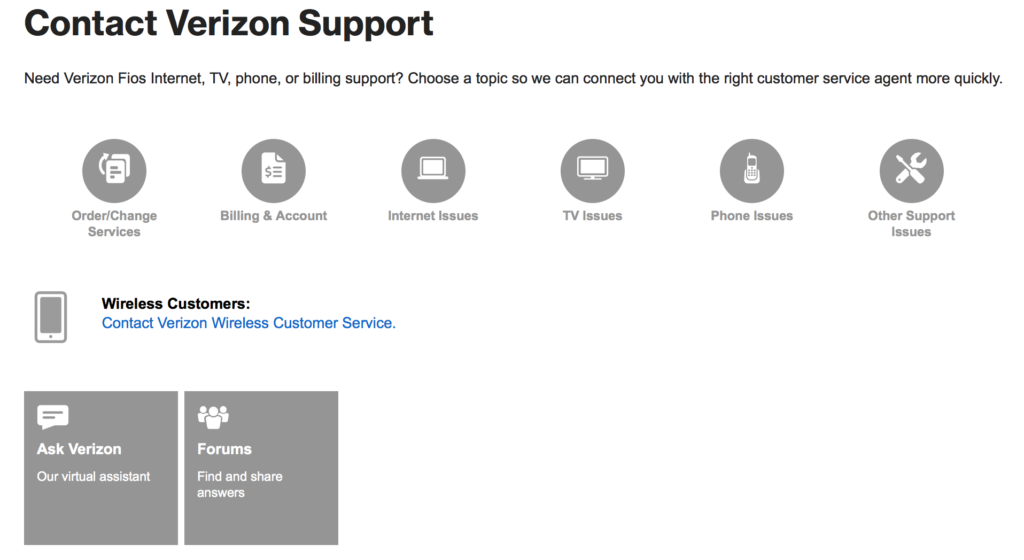

Here is what happens when you go to the Verizon website:

It takes you to a page with no login link.

You click the Phone link and it takes you to the home page. There is a login link in the upper right corner of the screen, where it should be.

You log in, but it doesn’t recognize your password. I know it didn’t recognize my password last time and the time before that. I figure this has to be my fault, I must be entering the wrong password, but I can’t think of another website where I have to so methodically reset the password every time I visit. I have an entry in my password list for Verizon, could it be outdated? No way to know what the matter is, but this happens every time at this website.

It asks me a security question. Where did I meet my wife? I know the city name, the restaurant name, the security answer I usually enter to answer security questions, the answer which has nothing to do with the truth. All are wrong.

It offers to reset my password. I enter my username and zip code. It prompts me to text or email a temporary password. I say Text.

I’m texted a temporary password.

I enter my username and temp password. I am then prompted to enter my a new password and confirm it. I enter the old password twice, meeting the requirements of capital letter, lower case letter and at least one number. At least eight characters overall. Now my password list is right, I think. I press enter and am prompted to choose a security question.

I do so, choose a new one not involving my spouse, and am prompted to log in. I type my username, click sign in, and am prompted for my password.

I enter my password and am told that the user name/password combo doesn’t exist. I want to scream, then notice that autofill is adding a y to the beginning of my username. Maybe this is on me, my browser, some past typo. I don’t know. I have to click the x on the autofill tab to advance to the password page.

I type in the password, click sign in, and am taken to the security question page, which I answer flawlessly. I’m finally in!

I click Billing. I’m given the choices to View Bill, Pay Bill, Payment History, Auto Pay, Paper Free Billing.

I click View Bill and am told my account has been disconnected, and I will remain in Auto Pay for my final bill(s). My final bill should have covered 12/13 to 12/20, but instead covered 12/13-1/12, so I need to arrange a refund.

I can’t find a telephone number to call, there isn’t a telephone number to call, so I contact the automated Virtual Chat. I type “I need to arrange for refund for overcharge on bill.”

Nothing happens. I realize this might be an issue with Chrome, with a security setting that suppresses popups, so I move over to Safari. I am able to log in directly. I ask the virtual chat the question and am given a link to the View Bill page. Grrrr. I was there already.

I find a menu item at the bottom of the page for Billing Disputes.

The link takes me to a page called

Billing Disputes.

It tells me I need the date of my bill, the amount of the charge, the label of the charge, the page number from the bill, and the reason for my dispute.

There is a link to contact Verizon. Clicking it takes me to a page that shows this (click to enlarge):

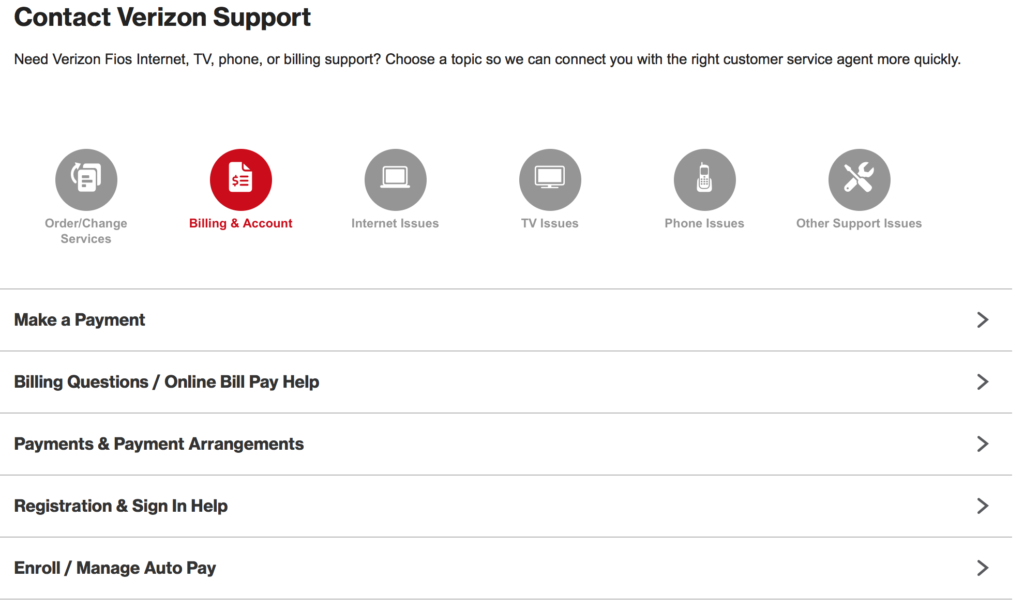

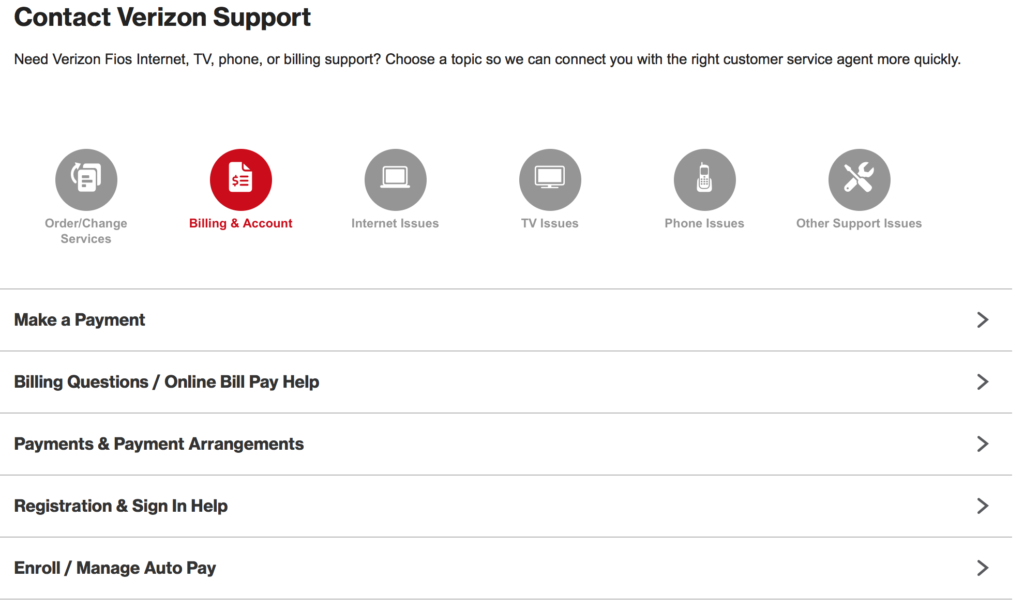

I click Billing & Account, which brings me to this:

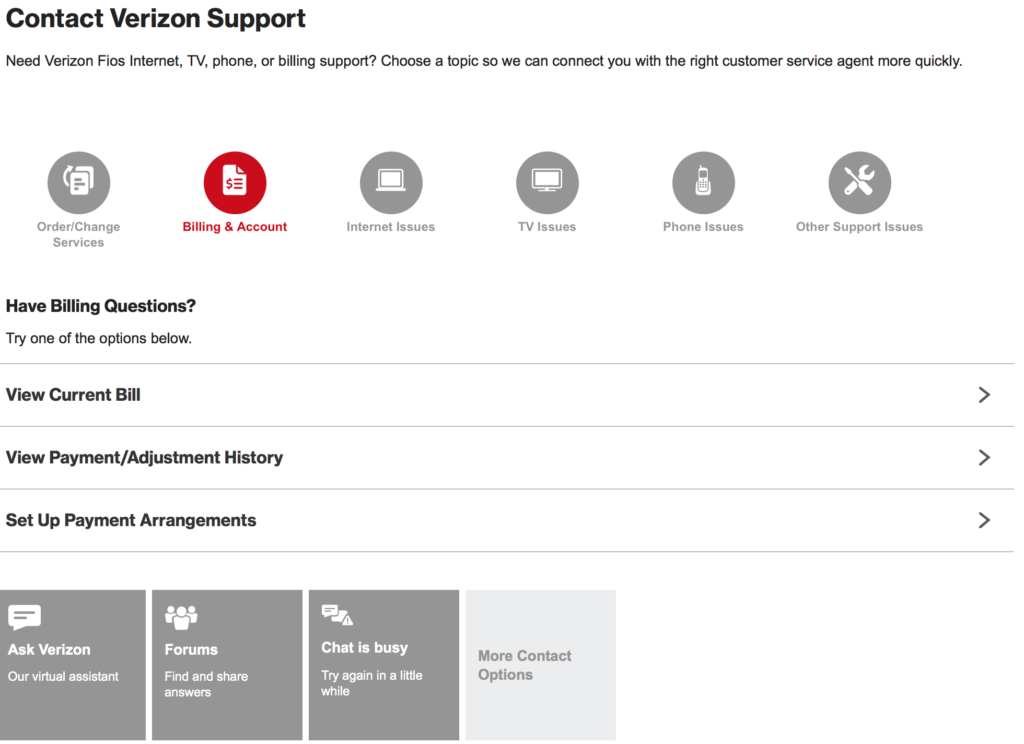

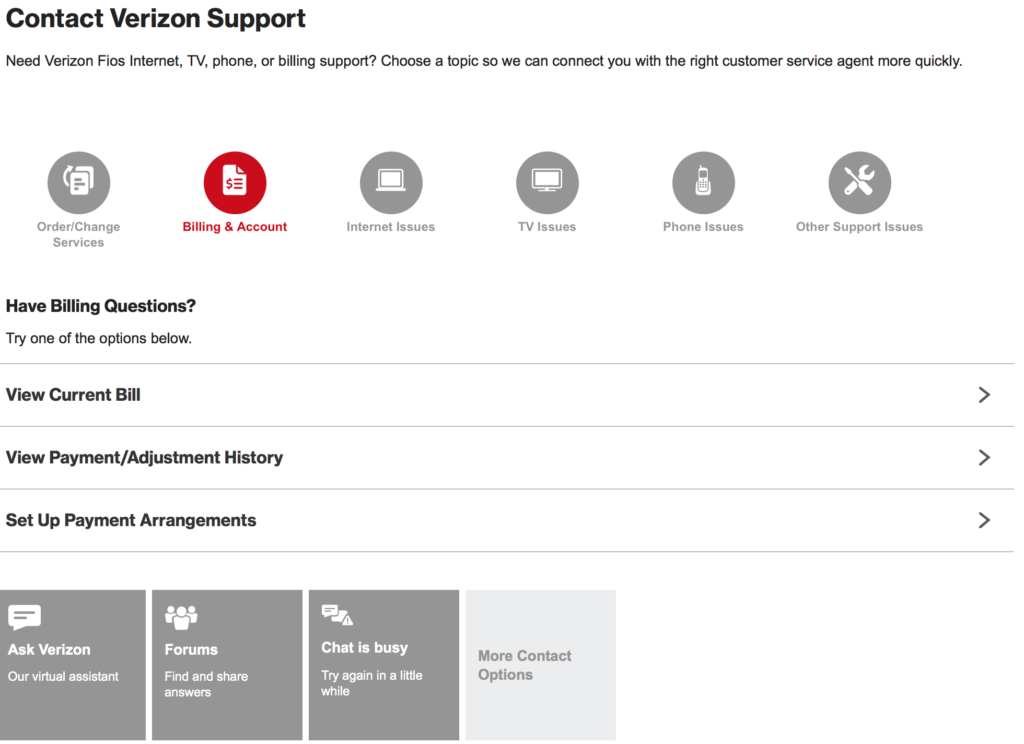

I click Billing Questions, which brings me to this:

Grrr! No phone number. No link to Billing Disputes after many links starting with the prompt Billing Disputes.

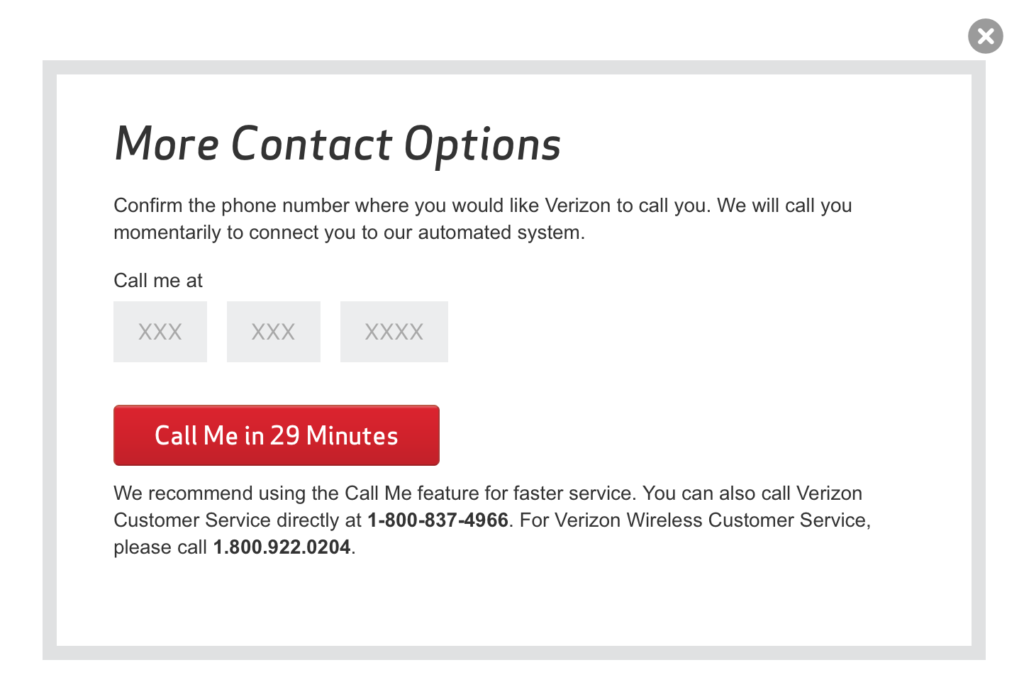

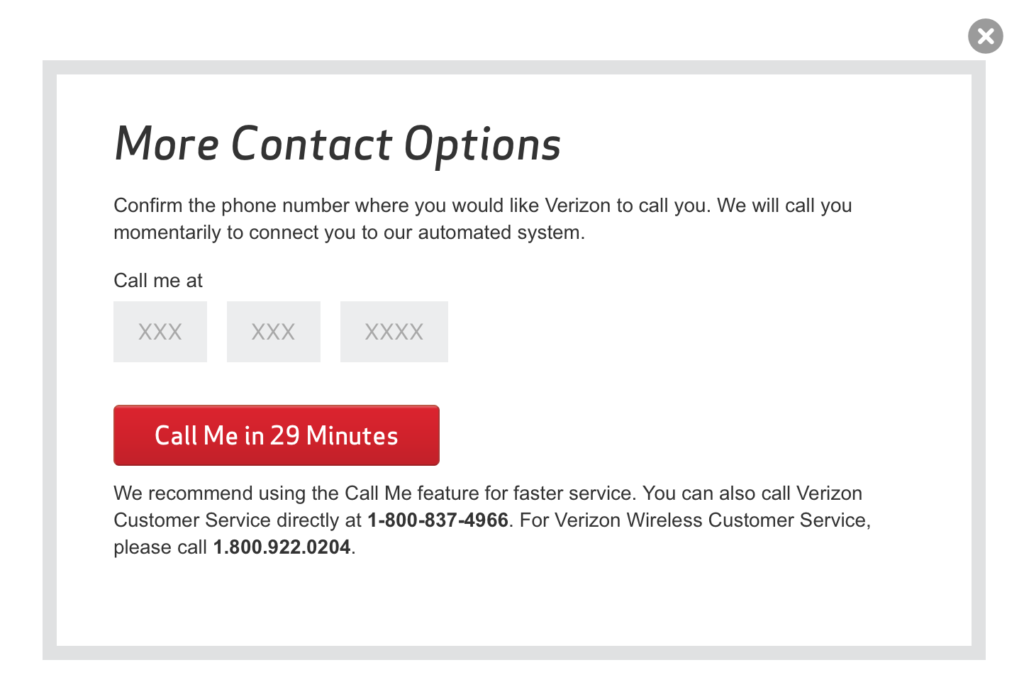

I’ve already been given the runaround by the virtual helper. Forums won’t help. Chat is busy! Hmm. More contact options. I click that.

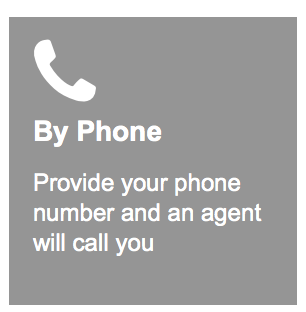

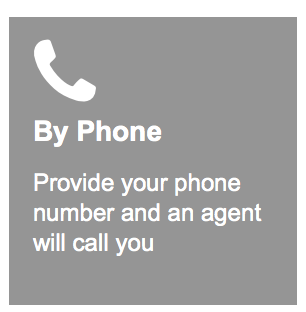

Click that and the button changes to this:

I click that and am given this:

But I don’t think the one I saw said Call Me in 29 Minutes. What I know is that I entered my phone number, but made a typo in the area code box, and it would not let me delete it. Not by back spacing, not by using delete, not by highlighting and typing. Nothing.

So I X’ed out, reopened the form and made sure to type my phone number correctly. I clicked the Call Me button and my phone rang immediately.

Wow, that was fast. But it wasn’t a person. It was a voice recognition system which asked me if I was calling about the number I was calling from.

No, I said.

What is the number you’re calling about?

I give the number. There is a whirring sound, like a robot thinking, and then I’m told that the account has been found and I’m prompted for the four number PIN attached to the account.

I don’t know the PIN. This happens every time I contact Verizon, no one ever tells me what the PIN is, they can’t tell me what the PIN is, but after a really frustrating time we always proceed. In this case, the voice prompts for the PIN. I give the PIN I often use for low-security accounts (not banks etc), and am told that’s not right.

Will I give another PIN?

No, I say.

Okay, the voice says. We’ll proceed without a PIN, but you may be prompted to answer some security questions later.

I’m given a list of menu items that seems familiar: Hear billing amount due, pay bill, recent transactions, anything else.

Anything else doesn’t help. I say Customer Service.

Would you like to speak to a customer service representative?

Yes.

I’m then prompted for the three digit number that appears on my bill next to the phone number. I start to say One and the voice interrupts me. I stop, listen to the prompt, then say One Seven Six.

The voice says back: DId you say One One Seven Six?

No.

Please read the three digit number that appears on your bill next to your phone number.

One Seven Six.

I’m transferred to Ashley, who answers the phone, Verizon Financial Services.

Ashley listens to my problem, says she’ll take care of it and puts me on hold. I’m on hold a long time, listening to terrible music, but she jumps back in a few times to apologize for the delay. It is okay.

After about 10 minutes she tells me that Autopay has been turned off. I ask if my card will be charged back for the balance I shouldn’t have been charged for and she says it will.

She’s very nice and helpful. Just as the man was who turned off my service two weeks ago, the man who said I would be billed for the useage in a final bill and I didn’t need to do anything else, was.

So, we’ll see.

Verizon is a giant company offering services to vast numbers of consumers. In my experience, over many years as a phone, wireless and internet customer, the website has always been a user interface disaster. The thing you need is always hidden, the pages take you to endless loops of not the information you want. The account page is sparse and not helpful.

On my page, a view of past bills, shows no past bills.

The messaging system deletes messages after 15 days, so you have no record of your interactions.

The chat system, when it’s working, doesn’t allow you to easily save the chat.

This utter disregard for the customer experience has to be designed into their service intentionally. It must be working for Verizon, in some cynical bottom-line way, but it is lousy and I’m glad to have finally moved on.

Spectrum, the new combined Charter-Time Warner service, is paying attention to customers now.