My father handed me the salt and pepper notebook and three chunky white dice, cubes with bold black concave circles called pips on each side. The dice were old, their white ivory yellowed with age, but they were heavy, substantial in a way that the dice that came with our Monopoly set weren’t.

My father handed me the salt and pepper notebook and three chunky white dice, cubes with bold black concave circles called pips on each side. The dice were old, their white ivory yellowed with age, but they were heavy, substantial in a way that the dice that came with our Monopoly set weren’t.

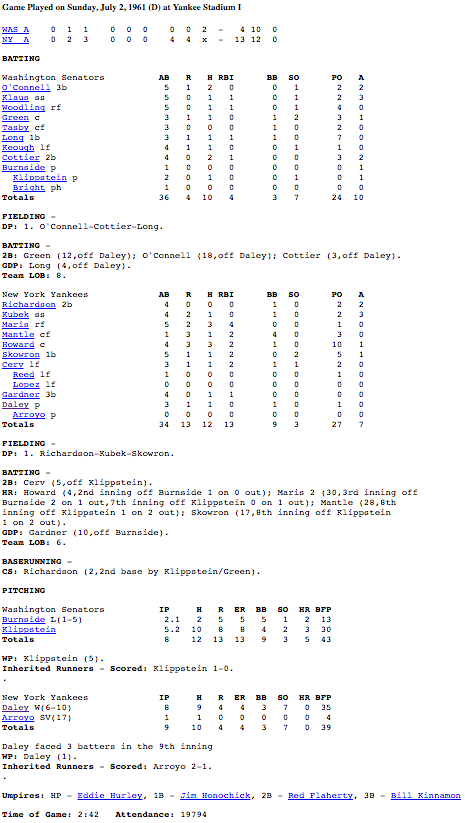

Inside the notebook, each page was a hand-drawn baseball scorecard, rendered in my father’s elegant calligraphy, and filled in with the notes and marks he used for scoring a game. Beside each scored game was pasted that day’s yellowed newsprint box score from the New York Daily News, underneath the date the game was played.

My father explained to me that he’d come up with the idea for his dice baseball game when he was fifteen or sixteen. Obsessed with baseball, he figured out how often players walked, made hits, hit home runs, on average, and so he populated the possibilities of the dice rolls with the appropriate number of walks, hits and home runs, plus doubles, triples, ground outs and fly outs.

Here’s how the game worked:

First you rolled one die. A one or a four was a strike. A two or a five was a ball. A three told you to roll two dice. A six told you to roll three dice.

When you rolled two dice, the lower die always came first. So, the order from lowest to largest would go: 1-1, 1-2, 1-3, 1-4, 1-5, 1-6, 2-2, 2-3 and so on up to 6-6, for a total of 21 outcomes.

When you rolled three dice, again, the lower die always came first, then the next lowest, and then the highest. That added another 56 outcomes, for a total of 77. It certainly seemed like a lot more back in the day.

My dad could have stacked the game events up. Since batters make hits about 22 percent of the time, he could have made all but four of the two-dice rolls hits (22 percent of 77 is 17) and all the three-dice rolls outs, but he didn’t. Which made the game more fun, because there was a little suspense while looking up the result of many of the rolls.

While I quickly memorized the codes for home runs (66, 666, 256) and triples (111), other rolls weren’t clear until I found them on the game sheet. A roll of 126, for instance, meant turning the page over, scanning down the column, then, “Ouch, line out to third base, dang.” I would dutifully write the number 5 down in the appropriate box and move on to the next batter.

To play I would take the salt and pepper notebook from the shelf in my bedroom of our house in Smithtown New York. I’d pull the velvet bag of dice out of a drawer, and a pen and ruler from off the table. I would flop down on the floor in my room, onto the carpet by the bed, and carefully draw in the lines for the day’s scorecard, running the pen alongside the ruler. My lines were often but not always straight, usually parallel, but still somehow sloppy, so different from the fine work my dad had done back in his day.

The drawing of the lines took too much time, but there was no way around it. The game couldn’t start until the scorecard was ready. A few years later, I bought a real scorebook to record the game records, to make it easier. I’m not sure the scorebook was the cause, but my interest waned a short while later and that season was never completed.

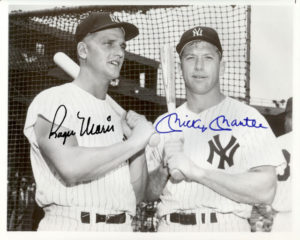

I would consult the Long Island Press, our daily newspaper, for the lineups and probable pitchers that day, and enter the Mets lineup versus whatever team they were playing. This was what my father had done, in his bedroom in New Hyde Park, 20 years before, following the schedule of the New York Giants in 1944. He was older than I was, 16 years old and in high school, when he invented his dice baseball game, but I could only imagine him bent over the notebook, furiously rolling the die into a cardboard box sitting on the carpeted floor.

“Strike one, ball one, ball two, oh! Roll three dice!”

Shuffling paper, a page turns, the three dice, bouncing off the box’s low sides and clattering to a rest haphazardly.

“One-two-five.”

Another page turn, paper swishes.

“Hmmm, ground out to second base.”

Pick the pen up off the floor, move to the scorecard and write 4-3 in the first inning next to Tim Harkness’s name. Oh, that was me, playing his game. He would write the result next to Ernie Lombardi’s name, or Mel Ott’s, in a statelier hand than mine, but with the same intensity, the same consciousness ensnared by baseball, devoted to recording the events of the game.