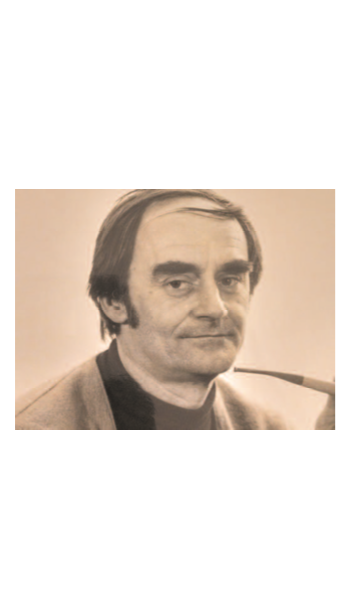

My father died in June, and my brother, Scott, and I travelled to Florida to help sort out his things, hold a memorial, and lay him to rest.

This isn’t the easiest thing to do, when a parent dies a lot of the thoughts you’ve had about your life and your parents boil up in surprising ways. It would be easy to cocoon, to deny the importance of keeping on and dealing with the dead in a physical way, to indulge one’s desire to wallow in the inevitable misery, but there were three reasons I came to realize it is better to deal more directly:

1) My friend John told me that when his parents’ died that the mundane activities that go along with the services and burial and traditions help you take a bit of control of the emotional wash.

2) In college I wrote a paper about Fellini’s Satyricon, and how the breakdown of burial rituals in the film presaged the moral and eventual physical decline of the Roman empire.

3) It is a lot better to do something than to think about something, at least in the long run.

The following is a scrapbook of some of the memories and thoughts from those days in Florida.

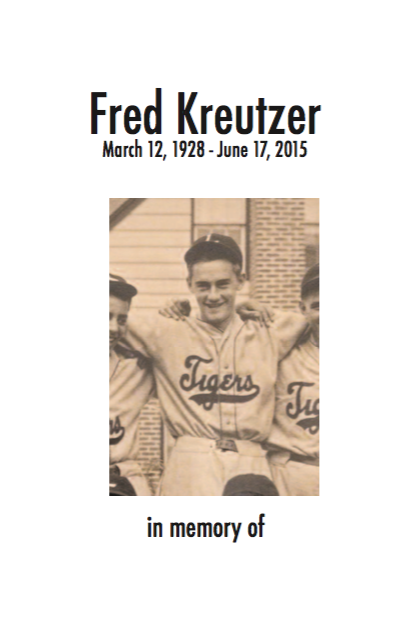

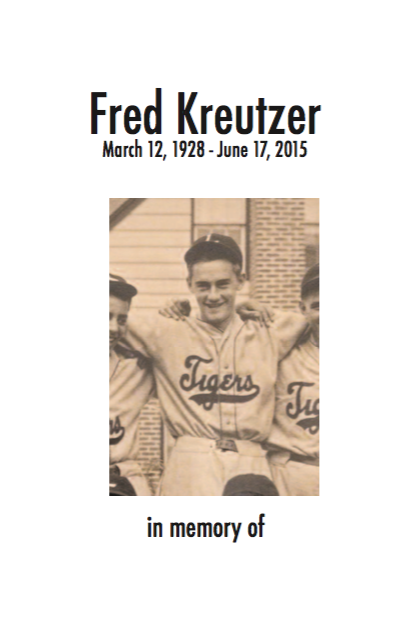

The program for the memorial service:

David Mark, our step brother, MC’d the memorial and did a fantastic job. We don’t have a recording of his remarks, which is too bad.

My wife, Elizabeth Royte’s, recorded remarks were played for the congregants. She asked that I not share them here.

I read mine out loud.

My dad was a carpenter. He renovated an old carriage house in Smithtown, New York, the house my brother and I grew up in, with exacting care, mitering the edges of paneling in the new playroom, for example, so they aligned perfectly with the formerly exterior shingles that made up one of the room’s walls. There were easier ways, but he didn’t take them.

My dad was a cook. Watching him stir together his Alfredo sauce was nearly as memorable as eating it, which I will not ever forget either. One of my favorite meals ever was at my dad and Diane’s house. They made fresh pasta, then swirled it in a pan with oil, garlic and anchovies. Simple but not easy. Incredible.

My dad was a teacher. He spent his career in a high school, in the gymnasium and in the classroom, teaching young people about sports and health and no doubt about their histories and our history and whatever other topics came up. Teaching was at his core, a process of give and take that was more than simply pedantic, and he never really stopped so long as someone near by wanted to discuss something and learn.

One time he offered to bet me some amount of something or other that I wanted. I got to choose, the Mets’ runs for the week added up or the Mets’ runs for the week multiplied. I chose the latter, and I’ve never since forgotten that any number times zero is zero.

My dad was a trailblazer. When I was a little boy my father would sometimes come home from work and too soon disappear behind the bedroom door. I could hear him talking on the telephone. I didn’t understand at first what was happening, I wanted to play with him. But I eventually learned that he was working with other coaches on Long Island to make soccer, an exotic game at that time, a part of the high school sports programs there. That worked.

My dad, when he was in the latter part of his career, took a sabbatical in order to earn his Doctorate of Education at Columbia University’s Teachers College. A large part of his mission was to help introduce modern communications and computer technology to his school’s curricula, years before that became a thing.

My dad was a nerd. He more than once told me proudly that his group of high school friends liked to figure things out, like how many paper clips would fit into the assistant principle’s office.

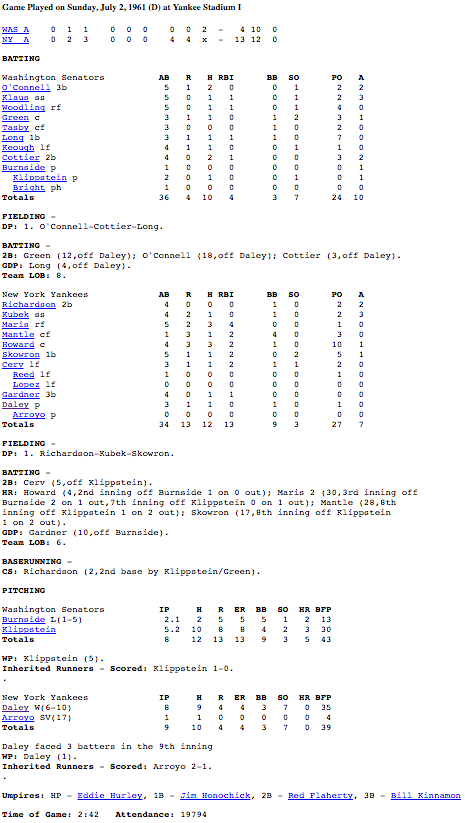

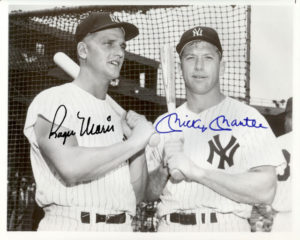

My dad was a phenom. While in high school, when not counting paper clips, my dad was the ace pitcher on the Sewanahaka High School varsity baseball team. He threw shut outs and struck out many batters against the largest and best schools at that time, and was treated in the press clips as one of the best high school pitchers on Long Island. He was recruited by many and eventually signed with the Boston Braves organization, selecting them over the Philadelphia Phillies.

My dad was a painter. For a while, at least. He created some copies, I think they were, of geometric paintings by Piet Mondrian, that hung in our laundry room when I was growing up. I’m sure there is a story that goes with this. What I know for sure is he made paintings.

My dad was a traveler. Although by the end of his life he didn’t like to leave Florida, when I was growing up we traveled all over the United States and Canada each summer. This landed us in Glacier Park in August of 1967, the night the forests glowed with hundreds of dry lightning fires and two women were killed by grizzly bears 50 miles apart. Over the years we drove across country, and at least twice up into Canada to Nova Scotia and the Algonquin Park. In later years, my dad traveled with Diane to Europe and Asia. His last big trip, if I recall correctly, was at the invitation of the South Korean government, on the 50th anniversary of the Korean War, because he had served in the US Army defending South Korea.

My dad was a patriot. He was proud of his army service, and his remains will be buried, as he wished, at the National Cemetery in Sarasota. Though my father was usually an even-tempered person, the one time I really made him blow up was because of the United States flag. It was 1969. I was going to Wilt Chamberlain basketball camp at Kutscher’s in the Catskills. For years I’d had a crew cut, administered with buzzing shears—my dad was not a barber, at least not in the skills sense—but now finishing up junior high, I had chosen to let my hair grow. I realized at this point that I needed something to keep my newly long locks out of my eyes while I ran up and down the court, and what could have been cooler in the days of Easy Rider and Woodstock and the Days of Rage than making my headband out of an old American flag I had in my room? I actually cut the flag apart and then sewed it back together into a very nice headband, but when my father saw it he was smudged with insult. He yelled at me, I fled and he chased me up and down the stairs, into my room and out again, around the yard even, him grabbing, me protecting, until at some point I relented and gave up my prize.

My dad was an architect. When he and my mom were considering buying the old carriage house that they eventually renovated, it was not obvious what the best way to set up the inside of the house was. My dad had some architectural training from school, and he taught me how to draft plans. I was encouraged to make drawings that showed how I thought the house should be set up, and I can say for sure that my second grade self loved being involved in the planning (though my desire to turn the grease pit in the living room into a pond with gold fish was not adopted).

My dad was a coach. When I was a boy my father spent a lot of time at the high school, coaching the boys’ varsity baseball team in the spring and the boys’ junior varsity soccer team in the fall. I spent a fair amount of time at his school when I was little, wandering among the massive athletes, hanging in my dad’s office, where someone was always popping their head in with a comment, a joke or a complaint. The air reeked of ambitious sweat and the floor was puddled from the dripping, showering athletes. I could go shoot baskets if I wanted, or jump on the trampoline, or climb up the rope, or kick the nubbly red inflatable ball against the wall, or up into the bleachers. There wasn’t anything much better for a six or seven year old than hanging out in a high school gym.

My dad was a counselor. During the early part of summer, he worked as the recreational camp director in Brookhaven. I don’t think I went with him every day, but I did many times, and I learned to play chess and shoot arrows with the bigger kids who let me tag along.

My dad invented fantasy baseball. Well, a game he called Dice Baseball. He gave me a chart that relied on the roll of a die and then dice, to determine baseball outcomes. As a schoolboy he used his Dice Baseball game to play the entire New York Giants’ schedule each day, pasting in the real box score for the day into the notebook in which he kept his Dice Baseball scorecards. I continued the tradition, playing New York Mets games each day, drawing the scorecards into notebooks just the way my dad did. The only thing was, his handwriting was way better than mine.

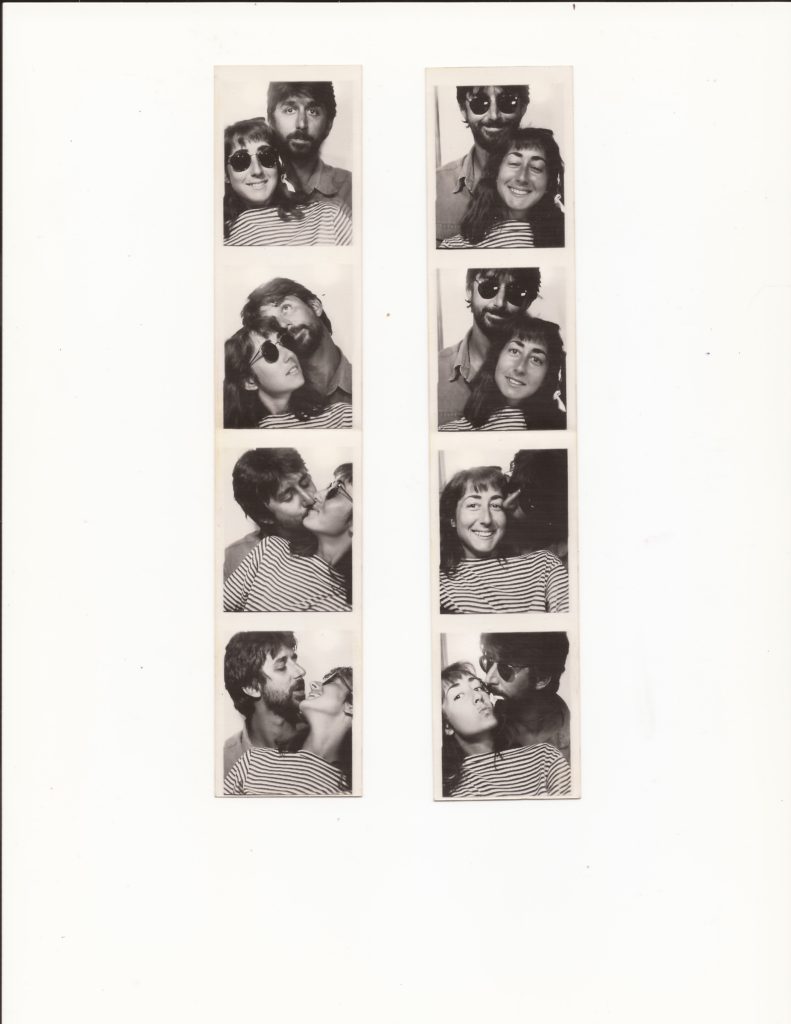

My dad was also a gardener, a photographer (ask Scott and me about our adventures developing film and printing in the little darkroom my dad built in the bedroom closet), a well-organized fellow who liked to work amidst messy piles. But most of all my dad was a father, my father, which is why I’m here today.

I love him and will continue to miss him, as I’ve missed him the past couple years as he became more and more a man who was just one sad thing with one sad mission to execute. I will regret those times, my inability to help and his inability to accept help, but in no way do they diminish the far better times spread over a long and colorful lifetime.

There were speakers from the Mens Garden Club of Engelwood, talking about my dad’s contributions writing and publishing the club’s newsletter for many years.

In a similar vein, someone from the Unitarian Universalist Church in Venice, spoke about how important Fred’s production of a newsletter for the fledgling congregation was, back in the days before they had a building, while developing a community.

And Diane, my dad’s wife, spoke about his life and his connection to a community that he didn’t always embrace. I think that was a lot of his story. He stood apart, a lot of the time, but also did what was necessary to move things forward. Diane wasn’t sure she would speak, and I was glad she did.

It was in the Unitarian Universalist’s lovely building in which the memorial was held, and they generously helped us set up a slide show and provided refreshments afterwards. It has been a while since I ate so many cookies. And they provided a generous place for us to share memories and thoughts about Fred.

At some point while thinking about my father’s life, at this time, I recalled him coming home from work one day talking about a short film that made him laugh out loud. It was a parody of Ingmar Bergman films called Da Duva. It was years later that I finally saw it, and recognized that it was Madeleine Kahn’s first film.

And many years after that I saw a production by my wife’s uncle, the director Robert Kalfin, which starred the other woman in Da Duva. I mention this because it perhaps explains why the movie came to mind. A fake-Swedish parody of Ingmar Bergman films about a bird and its poop? How does this pertain?

But it does. The wordplay, the scatology, the skewering of pretension, and the humor above all, laughing through the confrontation with mortality, are all a part of my father’s history and his character. I worried about the choice, that people wouldn’t understand, and was gratified how much the captive audience liked and got the film by its end.

The transfer is awful, but you can see and hear enough. It’s worth it.

https://youtu.be/8X2QmLWWxq4

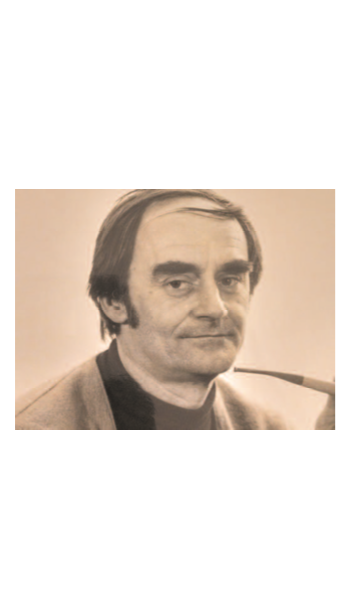

Photos from the slide who that day.