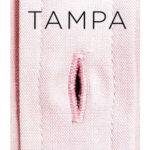

I came across the rather brilliant UK edition cover art, with the button hole, after picking up the far less vivid US version with the chalk writing.

I came across the rather brilliant UK edition cover art, with the button hole, after picking up the far less vivid US version with the chalk writing.

Celeste is a beautiful and wealthy young woman married to an heir to a great fortune who takes a job as an eighth grade English teacher because she has an unholy fetish for 14 year old boys. Needless to say, I hope, this is a story of Florida.

Nutting tells this story with velocity and with a fairly pornographic attention to detail, body parts and various fluids at least (oh, and the odors), but it is not at all realistic. Celeste is our narrator, tells her story with a psychopathic attention to her needs and motivations, and while she is aware of the difference between right and wrong, she filters that through her incessant need to stoke her sexual desire. Even though it’s wrong, and she knows that, she also knows that she can’t stop. Her needs are a part of her, and impossible not to pursue.

There are models for this sort of story. Celeste’s planning, her grooming and her seduction of her first boy, Jack, is told with florid, meticulous detail. Like Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Lolita’s narrator Humbert Humbert, Celeste’s narration of the story is a sales pitch and justification for her actions. Like JG Ballard’s Crash, Celeste’s desire is perverse and obsessive and relentless. Like Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, the first person narrator’s lack of moral objectivity is kind of thrilling. But there are differences, too.

Unlike Ellis, Nutting doesn’t seem to have a taste for grandiose satire. Her grotesques are small and acutely drawn, but don’t resonate across a bigger stage. Similarly, her ambitions are not nearly as large as Nabokov’s. This is a small story, grander because it doesn’t try to present any psychological rationale for our narrator’s obsession, but in the end it is a story that takes place in a nondescript American suburb that just happens to be in west Florida. (Based on a true story, at least in part, too.) And while Nutting’s sex scenes are very specific, they don’t approach Ballard’s obsessive attention to the most every detail in Crash. They are not about the larger machinery, the way the body melds into the modern technological world, but rather about the specific claims the body has on us as we dream, sometimes, of a larger world than ourselves. And one woman’s insistence none of that matters.

Celeste is an English teacher, and her class reads four books during the course of the novel. Romeo and Juliet, The Scarlet Letter, Lord of the Flies, and To Kill a Mockingbird. Each connects to the plot in some way, especially as a device for Celeste to talk to her young (14 years old) students in a mature way, about relationships and the possibility of sex, which excites them. But the novel undercuts these scenes by continually reminding us that Celeste has no vocation for teaching. What passion she brings is in pursuit of young, taut flesh that won’t tell. She really doesn’t otherwise care.

So this is a small, well told story about an explosive topic told in an explosive way. If you were to read it just for the sex scenes you’d cover most of the book, quickly and without regret. If you were to read it for the relentless horror, the way you might watch an episode of the Walking Dead, you won’t be disappointed either, though the amount of blood spilled is considerably less. But if you were to read it as a social satire I’m not sure you would wind up where you want to be. The elements are all there, some of the set pieces (one toward the end, especially, which is spectacularly pungent and hugely underplayed), end up being so low key it’s hard to tell what Nutting’s motivation is. Is this To Die For? Or something more.

My sense is she knows the story plays more sympathetically with the slighter scope. Her target isn’t as big as Ellis’s, the heart and loins are beggared by financial greed, and so she keeps is simpler. But she hits enough of the sweet spots, with enough gusto, that this small story starts to feel larger and larger as you think it through. Certainly a book that must be read by all Floridians.