A lot of people think that in his 2013 novel, Taipei, Tao Lin has written a great novel about contemporary life and love.

A lot of people think that in his 2013 novel, Taipei, Tao Lin has written a great novel about contemporary life and love.

I read his earlier short novel, Richard Yates, last summer, and enjoyed it. He has a style that is hyperselfconscious. His narrator in Taipei, Paul, is a novelist, and is continually aware of what is said, the context in which it was said, what was heard and the context in which it was heard. He evaluates each said thing and every expression and act based on all of it. Paul can be as tiresome as you might imagine.

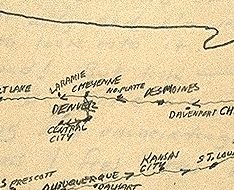

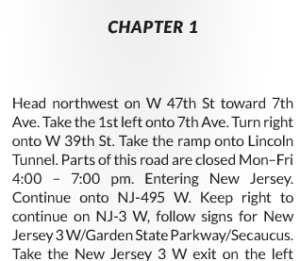

Paul grew up in the US, but his parents were from Taiwan and have moved back there. They like it when he visits, which he does a couple of times in the novel. But mostly he lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in 2010 or so. He’s interested in meeting girls, he’s recently broken up painfully, and his next few months will be spent on a book tour across America to support his most recent work (not clear whether it is poetry or a novel), and obliterating all sense of memory, so that all he has left is the memory of what happened in the last few moments. A quote from page 75:

Having repeatedly learned from literature, poetry, philosophy, popular culture, his own experiences, most movies he’d seen, especially ones he’d liked, that it was desirable to “live in the present,” “not dwell in the past,” etc., he mostly viewed these new obstacles (note: the long list of drugs he takes regularly) to his memory as friendly and, sometimes, momentarily believing in their viability as a form of Zen, exciting or at least interesting. Whenever he wanted to access his memory (usually to analyze or calmly replay a troubling or pleasant social interaction) and sensed the impasse, which he almost always did, to some degree, or that his memory was currently missing, as was increasingly the case, he would allow himself to stop wanting, with an ease, not unlike dropping a leaf or a stick while outdoors, he hadn’t felt before—and, partly because he’d quickly forget what he’d wanted, with a sensation of loss or worry, only an acknowledgment of a different distribution of consciousness than if he’d focused on assembling and sustaining memory—and passively continue with his ongoing sensory perception of concrete reality.

So, he’s kind of like the hero of Memento, except the obliteration of memory is self-inflicted, a way to escape the self consciousness he’s always felt and which he feels has robbed him in his life experiences.

At the same time, he’s brutally relentless in his self-examination of the moment, something his young girlfriend Erin feels from his ongoing descriptions of what is going on between them, from the perspective of most of the other players, and from himself. Paul is a proxy for Tao Lin, and he’s sometimes charmingly clever and often irritatingly self-involved. He is also very plain spoken and engaging, and the Russian dolls he unboxes page after page are sometimes comic, other times tedious, but his is a third person voice that is as immediate as the first person.

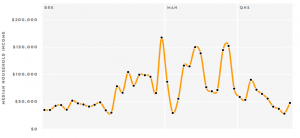

There is also quite a bit of apparent social content in Taipei. The characters are modern consumers of video, internet bandwidth and healthy foods (and guilt-out when they have to eat something that doesn’t meet their standards). Lin seems to be something of a critic of the consumer culture, or the way modern communications have fragmented us, but just as often the electronics are something more positive. The subtle satire is more the reader’s voice using Lin’s observations as evidence. Lin seems more a psychorealist in his intentions than a social critic.

Paul, Erin and their friends take Thompsonian (or Burroughsian) amounts of drugs, all the time, with very little worry about the mechanics of this desire. They call, the drugs arrive, for the most part, or are just there. There is hardly any concern about money, they never wait for the man, the context is not realistic but more like an extended dream of living a quasi-adult life with the emotional immediacy of a third grader. Paul also never talks about the history of writers who preceded him who have built personas or books off of drug use. Given the richness of reference, it is an odd omission.

Taipei is something of a schematic, a drawing board philosophical inquiry into the manner of memory obliteration, existential drug-fueled YouTube creation and love without the ability to express anything soft. Perhaps most curious is a passage in which Paul declares that his favorite novelist is Ann Beattie, and also Tao Lin’s (I subsequently read in an interview with Lin, who also listed Bret Easton Ellis among his favorite favorite writers). Paul’s favorite novel, he says, is Chilly Scenes of Winter. Remembering Beattie’s plainly declarative writing, I return to the Chilly Winter of those young lives trying to connect in another time of social upheaval, which doesn’t feel at all like Taipei on a superficial level, but once you get past the writer’s style makes them feel quite similar indeed.

Taipei is far from a great novel, but it is ambitious and idiosyncratic and often good fun. I like that sort of thing.